Landscapes of the Game

How golf has captivated and inspired artists through the ages.

Although one requires a lifetime spent in the sun, and the other requires a lifetime spent in the studio, parallels between golf and fine art run deep. Both demand an intimate understanding of form, whether in the elegant arc of a well-struck iron or the careful balance between light and shadow on canvas. To conquer a golf course, one must perceive what others cannot — the contours of the environment, the pockets of interest and the infinite gradations of green. For both great golfers and great artists alike, it is about seeing details others may miss and bringing them together into something extraordinary.

“View of St Andrews from the Old Course” (1740) by Unnamed Artist.

While the intricacies of the game provide plenty of intrigue, fine artists also arrive at golf as a subject because, quite simply, fairways are gorgeous. The game itself is an art form, and so is the design of the course, which is shaped around the contours of the surrounding environment. Brannen Veal, Director of Golf at Sea Island, is consistently amazed by the artists who visit the resort and what they produce after they observe the legendary courses. “Artists tend to capture a view that nobody has really ever seen, or certainly I haven’t,” Veal says.

There is no definitive genre of golf art — unless you count the game itself as fine art, which to many aficionados would be fair. Golf has served as an inspiration for artists ranging from Rembrandt to James McNeill Whistler to Norman Rockwell, all of whom saw something universal not only in the beauty of the game and its fairways, but also in what it has said to them about the human condition.

AN ART FORM AS OLD AS THE GAME

Fine art depicting golf preceded the codification of the rules of the game we play today. Rembrandt, the Renaissance Dutch artist best known today for his moody oil-paint masterpieces, carved just over 300 etchings in his lifetime. One of which is “The Golf Player” (1654), an etching of a man playing golf just outside of a country inn while another man lounges on a bench inside. His inclusion of a golfer in one of his works points to the fact that the sport, known as kolf in the Netherlands, was popular enough to appeal to a mass audience.

“The Golfers” (1847) by Charles Lees.

This long-storied tradition of the golf landscape in painting, which is still practiced today by many artists, was first established by “View of St Andrews from the Old Course,” a painting by an unnamed artist in 1740. Depicting the venerated Scottish fairways as a series of undulating hills, bordered by cliffs overlooking the freezing water of the North Sea and presided over by the medieval town of St. Andrews, one can very well imagine the artist at work. Much like Linda Hartough, a painter who has captured Sea Island Golf Club among many famous courses, the unknown artist likely approached their craft with the same reverence. “What I put into a painting is what I want you to experience as the viewer,” Hartough says. The unnamed 18th-century artist wanted to capture the game, but also the wind, the bleating sheep, the salt air, the distant noises of industry, the sense that the world is there, but in the periphery.

“Every single course has a unique look,” adds Hartough, whose collectors include Jack Nicklaus, Sea Island, the United States Golf Association and the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews.

THE HUMAN ELEMENT OF GOLF

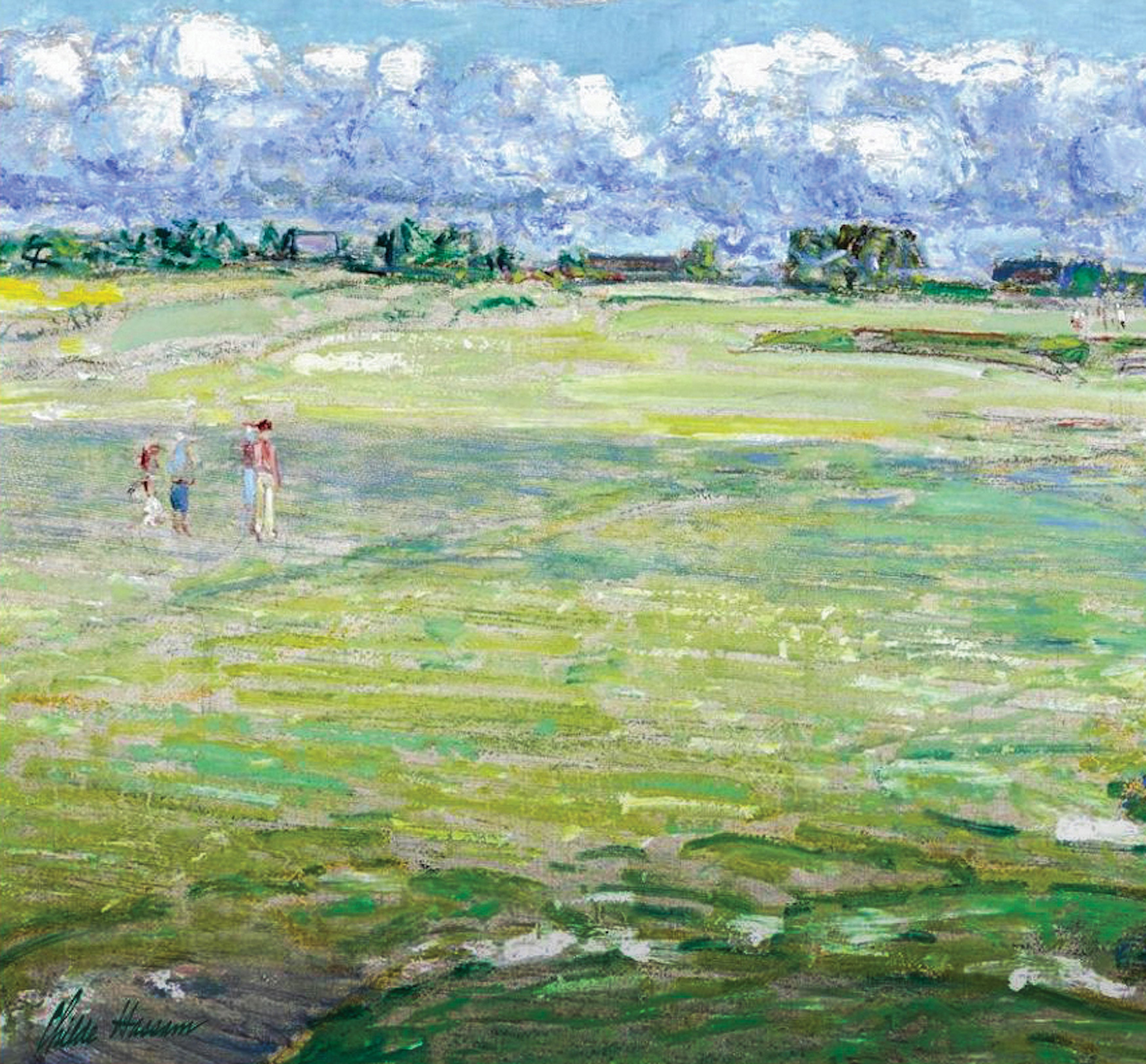

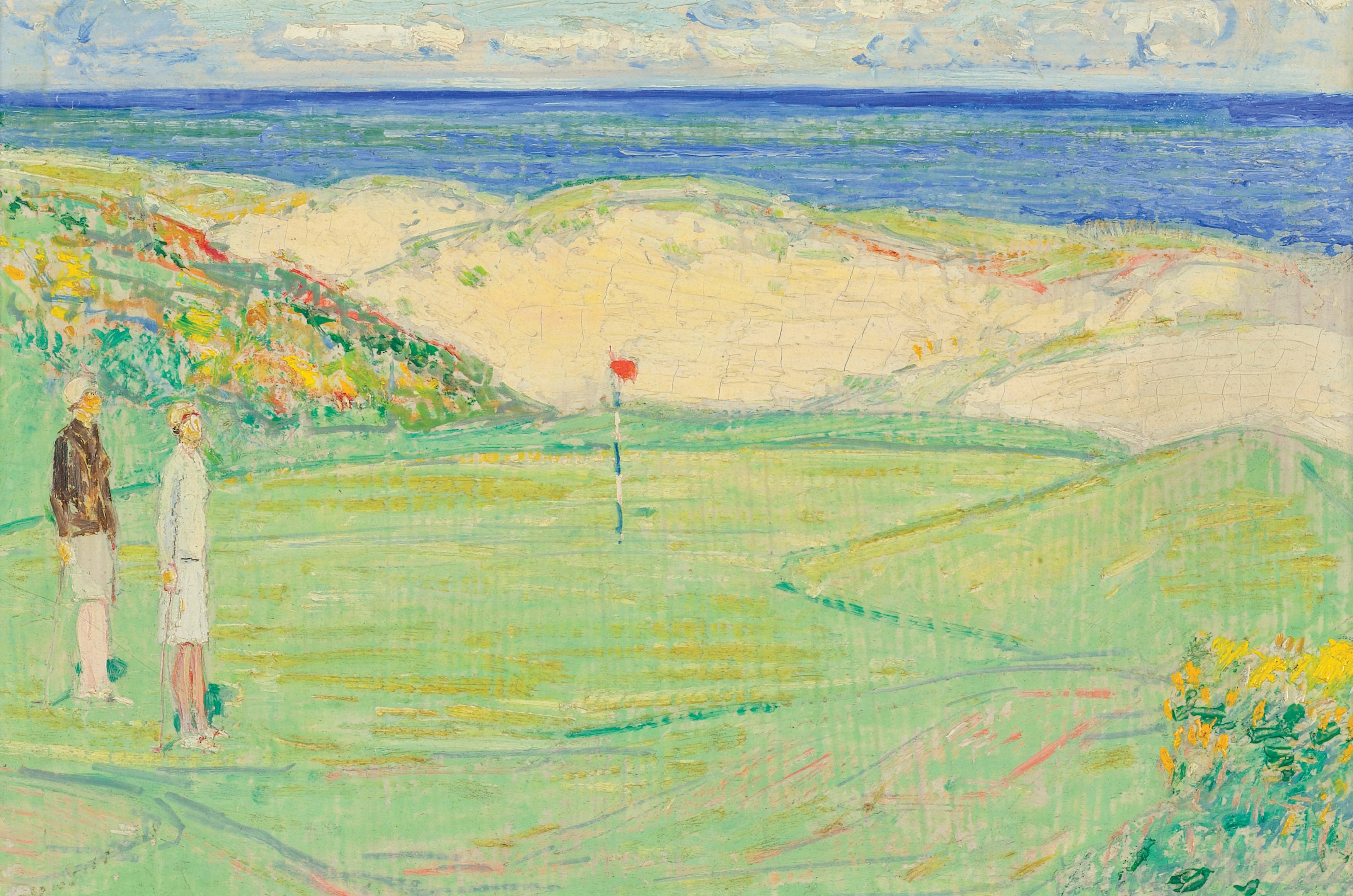

The manicured greens, themselves masterpieces of architecture and design, have inspired some of the most renowned landscape painters of their day. These include James McNeill Whistler, whose watercolor “Grey and Silver: The Golf Links, Dublin” (1900), captured the stormy skies over a greenway in Ireland, and Childe Hassam, who captured American golf courses at the beginning of the 20th century in loose, pastel-tinted strokes that hinted to the pleasure of the game for those who engaged in it for recreation.

(left to right) By Childe Hassam, “Golf Links” (1962); “East Course, Maidstone Club” (1926); “Two Hickory Trees” (1919).

Golf, as those who play it can attest, is not merely pretty. It can be impossibly frustrating, maddeningly elusive and also one of the best ways that human beings can connect in a common pursuit. The complexities of the game are perhaps best captured by Charles Lees, a Scottish-born painter, in “The Golfers” (1847). This piece is a complex and crowded canvas of over 50 figures standing over a decisive moment, a ball hanging on the edge of a hole, in a match at St Andrews Links. All of the drama inherent in the game is present in the composition — a squirming caddy, a rules official with pince-nez in place, a tense player and his partner willing the ball to fall, their cocky opponents and even a disinterested group of gossipers on the fringes of the crowd.

Evan Schiller

Norman Rockwell, himself an avid chronicler of human life in the post-war United States, often used golf as a subject, including in “Four Sporting Boys: Golf (Missed)” (1951). It depicts yet another missed putt, this one attempted by scroungy boys with grass stains on their white pants. In doing so, he brought the sport into the mainstream, just as Rembrandt did with his etchings in the 17th century.

While Andy Warhol highlighted the fame and glory that can come with the sport in his 1977 painting of the golfer Jack Nicklaus, which was auctioned for $1.1 million in 2024, contemporary artists continue to emphasize, in their own aesthetic languages, that golf is more than an elite pastime.

“Jack Nicklaus” (1977) by Andy Warhol.

A PLAYER’S BEST SUBJECT

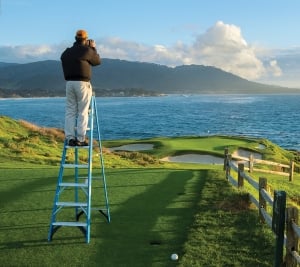

Sometimes, those who are best equipped to appreciate the sport as fine art are those who know how to play it best. Photographer Evan Schiller, for example, was first inspired to take photographs of golf courses in 1986 while playing in the California Open as a PGA Golf Professional. “My buddy and I got to the ninth hole, and I looked out at the scene in front of me and saw that it was so beautiful,” he says. Later that day, he bought a camera and quickly established a career as a professional photographer. To date, Schiller has photographed over 600 championship golf courses, and names Ocean Forest Golf Course on Sea Island as one of his favorites.

Sea Island Through Artists’ Eyes

Sea Island remains an important place for golf artists. Lee Wybranski, celebrated for his official posters of major golf events, including the U.S. Open, creates work redolent of the Art Nouveau style of graphic design. He remarked that he couldn’t believe his luck when he was commissioned by Sea Island to capture the golf courses. “When you get into golf, you hear about places like Sea Island,” he recalls. The history of the links, which were first designed by Walter Travis in the 1920s, and recently updated by Davis Love III and his brother Mark, inspired him to create paintings that capture the unique landscape, including the Spanish moss dripping from the trees surrounding the 18th hole, and The Lodge that overlooks it.

“The Lodge at Sea Island No. 18” (2006) by Lee Wybranski

Golf Course Photographer Evan Schiller has traveled to hundreds of championship courses throughout his career. The Ocean Forest Golf Course on Sea Island remains one of his favorite places — not only to photograph, but also to play on. “It has a certain vibe to it, a certain tranquility,” he says. “There are holes that go through the woods, and holes on the water. There’s bird life, lakes and valleys. There are houses, but you can’t really see them. It’s just really so wonderful.” He adds that the course is even better after the Beau Welling Design refresh in 2023, and that The Cloister is his favorite hotel in the world.

When Linda Hartough was first hired to paint the Seaside Course, she chose the 13th hole. “It just seemed to me to be the most deceptive,” she says, adding that the confluence of marsh, creek, skyline and green added a lot of intrigue to the overall composition. Hartough especially loves the Sea Island fairways in autumn. “My favorite time of the year is October, when the marsh around the courses turns golden,” she says. “I sit there for hours on end, just observing.” As a viewer of her work, you sit there with her. “Every time I look at one of Hartough’s paintings, I discover something different,” says Veal.

Werner Bronkhorst; “A Day On The Green” (2025) by Werner Bronkhorst.

The game continues to inspire those who enjoy it, even in the digital age. South-African-born artist Werner Bronkhorst creates heavily textured paintings of athletes, including tennis players and surfers, which have garnered him over 1.5 million followers on Instagram at just 24 years of age. He recently shared that golf is his favorite subject. “You have to rely not only on your skills but also your judgment of course layouts and the elements to get a small ball in a small hole with as few strokes as possible,” he wrote in a recent Instagram post. “It’s not too different from what I try to achieve in my own art.”

Mirroring the nuances of golf, Bronkhorst captures rhythm, timing and flow to awaken his illustrations of painted landscapes. A deep understanding of each thick texture is required in Bronkhorst’s work, similar to how a golfer must recognize the environment, course and their stroke to achieve greatness. “Timing can mean the difference between a bad texture or a really clean finish. The rhythm required to push the paint around the canvas has to be swift and elegant. I feel like I’m a golfer when I paint!”

THE ESSENCE OF THE COLLECTOR

“Seaside Course No. 5” by Evan Schiller.

Lee Wybranski

Lee Wybranski, whose exquisitely joyful Art Deco-inspired posters and paintings of championship golf courses are collected by Rory McIlroy and Jordan Spieth, notes that many of the people who buy his art don’t even play the sport. “Golf has wide appeal, but at the end of the day, it’s not just about golf,” he says. “It’s about the feeling and atmosphere that’s created.”Photographer Evan Schiller echoes this perspective, emphasizing that what draws in both collectors and viewers is the vision behind the works. “The difference for me lies in the extent to which one is willing to go to capture a moment in time that will never occur again. It’s seeing and anticipating beyond what is ordinary. There is a huge difference between looking and seeing, and I think the art is in the seeing,” said Schiller.

Pieces that can evoke feelings of timelessness and beauty, encapsulate the same emotions held by onlookers as a golfer raises his club to swing. There is a higher purpose served by artists and golfers alike, a display of cherished refinement. “Golf instills in people honor and tradition,” says Hartough. “People collect my work because they love the game, but also because they appreciate these virtues.”

Bobby Jones said it best, “Golf, after all, is the closest game to the game of life.” Art is simply the vehicle best equipped to capture its complexities.