Looking Back

President Jimmy Carter’s lasting imprint on the Georgia coast.

American presidents have long sought a secluded refuge away from Washington, D.C. For Thomas Jefferson, it was his mountaintop retreat at Monticello. For Franklin D. Roosevelt, it was the warm, mineral-rich waters of Warm Springs, Georgia. George H.W. Bush often returned to Kennebunkport, Maine. His son, George W. Bush, found peace on a ranch in Crawford, Texas.

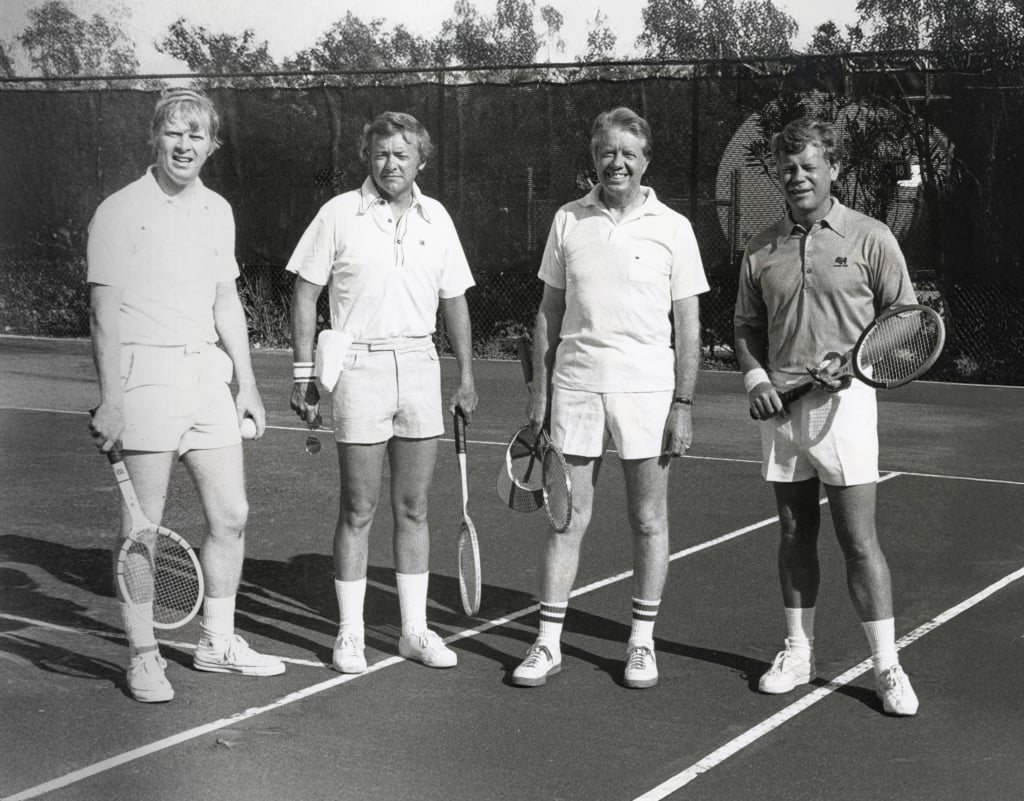

Carter playing tennis at Sea Island, 1976.

For Jimmy Carter, however, it was Georgia’s Golden Isles, where he became attached to the wild and windswept marshlands. Georgia’s barrier islands were not mere destinations for the peanut farmer from Plains; they were places where the tides moved slowly, conversations with trusted friends flowed easily and the weight of public life lifted.

It was also here, at The Cloister in 1976, that Carter gathered his newly named cabinet for a historic, pre-inaugural meeting. Beneath ancient live oaks and Spanish moss, the incoming president began shaping the course of a new administration.

“Since its opening in 1928, Sea Island has welcomed many notables, including U.S. presidents, foreign heads of state, celebrities and European royalty, most of whom visited to enjoy leisure time,” says Mimi Rogers, Sea Island Archivist. “Jimmy Carter spent time on Sea Island before the election, and, as the first president from Georgia, he understood that The Cloister provided the perfect setting for the first gathering of his cabinet appointees.”

(left to right) Jack Carter, Dr. Carlton Hicks, former President Jimmy Carter and Jim Bishop, Sr.

Carter’s connection to the coast ran far deeper than politics. These marshes, barrier islands and estuaries formed the backdrop of a lifelong devotion — one that would leave an enduring environmental legacy from Ossabaw to Cumberland.

A VOICE FOR COASTAL GEORGIA’S WILD PLACES

“My thoughts on conservation are grounded in a lifelong love of the natural wonders of Georgia,” Carter once said. That love translated into action, helping to preserve some of the state’s wildest and most beautiful places, especially along Georgia’s 100-mile coastline.

In 1967, Senator Carter became a charter member of the Georgia Conservancy, through which he strongly advocated for the protection of Cumberland Island, Georgia’s largest and southernmost barrier island. As a result, it became Cumberland Island National Seashore in 1972, when Congress established it to preserve the island’s natural and historic resources.

As governor, Carter created the Georgia Heritage Trust to preserve properties throughout the state that possessed unique natural characteristics or historical significance. Ossabaw Island was the first property to receive protection under the program in 1978. Carter, as president, helped facilitate the sale of the island to the state as a Heritage Preserve.

Perhaps the most impactful legislation protecting the Georgia coast was the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act of 1970, securing approximately half a billion acres of Georgia’s salt marsh from development. While the legislation was signed by his predecessor,

Carter championed the act as governor when he took office in 1971.

As a state senator (1963-1967) and later as governor (1971-1975), Carter “was very involved in that process to support the initiative,” says Buddy Sullivan, Senior Historian for the Coastal Georgia Historical Society. “He was very, very supportive of the movement to conserve the coast.”

A PERSONAL CONNECTION TO THE COAST

Carter’s relationship to the coast was also deeply personal and restorative. He could rest and unwind and fish in relative isolation, far away from the demands of Atlanta or Washington, D.C., where he enjoyed the company of trusted friends who lived on St. Simons or Sea Island.

Carter planting his commemorative oak tree at The Cloister, 1981.

“He found sanctuary down here,” says Jim Bishop, Sr., a Sea Island resident and decades-long friend of Carter’s. “He found a place he could really enjoy without the whole world getting involved. He could sit down and talk to me and his other friends about anything in the world and not be afraid it was going to get around.”

Bishop, a lawyer, first met the future governor and president in 1967. Carter, who unsuccessfully ran for governor the year before, came to St. Simons Island looking for help and votes for the 1970 gubernatorial campaign. Bishop was able to help Carter make connections with key constituencies on the campaign trail, like the local unions, and win the 1970 election. Thus began a friendship that spanned decades.

Bishop spent more nights than anyone else as Carter’s guest at the White House. Over the years, they often went fishing together.

“He loved fly fishing,” Bishop says.

When visiting the coast, Carter also loved spending the night at a friend’s house on Sea Island, especially back in the day when he was campaigning.

“He established a personal relationship by doing that,” said Bishop. “He’d arrive late, but not too late. He’d supper, as he called it. He’d chit-chat. And then he’d finally say, ‘I don’t want to keep you up too late,’ and he’d go to bed and then wake up early, make his bed and leave.”

A LIVING LEGACY

After his presidency ended, Carter returned to the resort in 1981 to plant a commemorative oak tree at The Cloister as part of the resort’s tradition of honoring world leaders. This tradition dates back to 1928 with President Calvin Coolidge and Sea Island founder Howard Coffin.

“Carter had an appreciation for the history of the hotel and what it meant to the Georgia coast,” says Sea Island historian Wheeler Bryan.

The President Carter Oak at The Cloister

The commemorative oak is a living emblem of the former president’s deep connection to the region, but his legacy is more than symbolic. If it were not for Carter, the Georgia coast would look much different from what it does today.

“Governor Carter was one of the reasons why there’s so much protected land on the Georgia coast,” says Sullivan. “He supported it and got behind it both in his public life and in his private life.”

Bishop agrees, saying, “His legacy has got to be significantly environmental because of Cumberland Island and his support of the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act. In our part of the world, I don’t think there is any more powerful legislation than protecting half a billion acres of marshlands that we enjoy around here every day.” And perhaps Carter said it best, “We are stewards of a precious gift.”

The day after President Carter’s passing in 2024, a guest at The Cloister, Will Kamensky, stopped by the oak tree Carter planted in 1981 and placed a handful of peanuts on the commemorative plaque below its outstretched branches. On his Instagram story, Kamensky wrote, “President Jimmy Carter planted a tree at Sea Island in the 1980s. Now it has grown into a mighty oak. As a Georgian, I obviously carry peanuts on me at all times. So I left some with the greatest Georgian’s tree this morning. He was America’s peanut farmer.”

This simple yet profound gesture captures how Carter’s life and legacy continue to resonate. His oak stands tall as both a literal and symbolic reminder of his Georgia roots and his belief in leaving the world a better place than he found it.