Mariner’s Compass

Telling the tale of seafarer's tools used to explore the globe.

Throughout known history — and likely long before — the siren call of the sea has proven irresistible; persuading explorers to set off upon its ever-changing surface and leave behind the relative safety of terra firma. The same insatiable need to discover what lies beyond the horizon has also provided incentive for the creation of tools to aid in such journeys and tendered a platform for the building of empires, expansion of cultures and global exchange of ideas.

Astrolabe tool

GUIDED BY THE STARS

Celestial navigation utilizes the position of known heavenly bodies including Polaris (the North Star), the sun, moon and constellations to pinpoint a vessel’s relative position. Before latitude, longitude and mechanical navigational devices had been dreamt of, early Polynesian societies studied the sky and the migratory patterns of birds. On nearby islands and coasts, Micronesian sailors shared their collective knowledge with seagoers through the creation of “stick charts,” assembled from shells and bark strips that laid out information they’d gathered regarding sea conditions. Displayed on the ground, these impermanent “manuals” were a way for sailors to exchange information with one another about the location of such features as shoals, islands, obstacles and currents.

Theories of how early Polynesian navigators reliably traveled to and settled among the multitude of islands that form the Polynesian Triangle were proven in 1976 when Micronesian Master Navigator Mau Piailug guided a traditional Polynesian double-hulled sailing canoe across 2,400 miles of open sea from Hawaii to Tahiti. To accomplish this feat, Piailug used traditional wayfinding techniques that included the angle of ocean swells, currents and celestial bodies as well as the observation of birds and fish and the direction in which they were traveling.

Insight into 16th-century seafaring and exploration, Jacques Devaulx, “Nautical Works.”

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

Along with dead reckoning — a formula of speed, distance and time — many inventions were developed to determine location. These include the gnomon, the part of a sundial that casts a shadow; the kamal, used in celestial navigation to determine latitude; and the quadrant, for establishing latitude, longitude and time. The astrolabe, developed by early Greeks, was used to locate celestial points, while the horary quadrant measured the time of day according to the altitude of the sun. Other tools, such as the theodolite, fix distance, elevation and angles, and the sextant provided the distance between a celestial body and a fixed point. Charts, too, became more sophisticated and portable; crafted from animal skins, plant fibers and paper, they contained fixed information that could be carried to sea.

Wind Surf, the flagship of Windstar Cruises in Capri, Italy

“Early and modern nautical charts require systematic and repeatable environmental and geographic observations,” says Phil Hartmeyer, Marine Archaeologist in the Ocean Exploration division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Hartmeyer adds that some of the earliest charts plotted depth readings taken from lead line, sounding pole and wire drag surveys — methods that required a physical connection between the reading at the bottom of the body of water, and the vessel taking the measurement. Seafarers relied on these soundings to safely navigate both new and familiar waters.

Navigation tools

For modern mariners, celestial navigation remains a fundamental skill, though often supplemented by advanced technologies. Neil Broomhall, Corporate Fleet Captain at Windstar Cruises, acknowledges its lasting significance: “Even in the age of GPS, knowing how to use a sextant is an essential skill. It teaches mariners to read the sky, understand their environment and navigate independently of electronic systems.”

Celestial navigation requires clear skies to take vessel headings. According to Hartmeyer, “The compass allowed mariners to use the earth’s magnetic field to take vessel headings on days when celestial navigation was obscured by weather or overcast skies. While the compass helped establish heading, the sextant could establish vessel position in physical space on a nautical chart.”

THE AGE OF EXPLORATION

There is general consensus among historians that the introduction of the magnetic compass as a navigational aid occurred in China around the 11th or 12th century. With the ability to determine the location of true north and true south, mariners set off with a new degree of confidence to map the world. By the 1500s, the Age of Exploration was underway in earnest. Europe’s major cities, located in deep, natural ports on sea coasts and the mouths of major rivers, developed into global trade centers.

Neil Broomhall, Corporate Fleet Captain at Windstar Cruises.

The need for more accurate and detailed maps grew as exploration expanded. Early maps, often based on limited knowledge, were rudimentary and often relied on secondhand reports. However, with the introduction of more reliable navigational tools, cartographers were able to make more precise charts of the world. These advancements allowed for the refinement of geographical knowledge, turning crude outlines of coastlines into more accurate representations of the continents and their features.

By the late 15th and early 16th centuries, maps began to reflect a clearer understanding of the world’s geography, which allowed explorers to chart longer voyages and reach more distant shores. The art of cartography, now informed by better data, became crucial in bridging the gap between exploration and global trade.

Even with new tools including the seagoing chronometer — a precise timepiece for determining longitude — navigational lights and the establishment of the Prime Meridian, the sea remained unpredictable and disinclined to negotiation; a place where even the most carefully laid plans could be foiled by a sudden wind or rogue wave. Yet, with each new innovation, sailors found ways to mitigate the sea’s uncertainties.

THE MODERN LIFE AQUATIC

As shipping and cruise line industries grow, navigational techniques continue to evolve. To successfully navigate the world’s wide seas, sailors must still learn the language of winds, tides and waves. More recent developments include onboard radio communication systems, echo sounders to determine depth and distance, long-distance radar and electronic chart displays and the addition of autonomous vessels for commercial shipping.

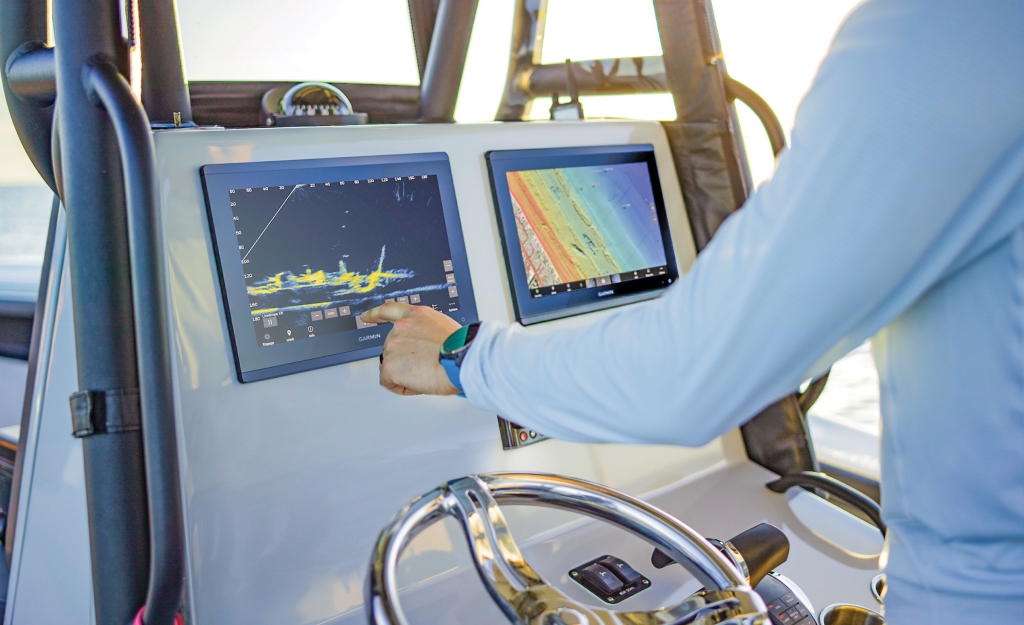

Garmin Livescope Plus

The most notable modern game-changer has been the introduction of Global Positioning Systems (GPS) and satellites, which provide a level of accuracy that would likely be the envy of early adventurers. Hartmeyer explains that GPS is commonly used across the planet, utilizing a network of satellites that send and receive positioning information to a vessel’s receiver, providing accurate and dependable location information.

Eyvind Bagle, Ph.D., Senior Curator, The Norwegian Maritime Museum, says that for the navigation of colossal modern-day ships, logistics companies and their mariners depend on high-end technological systems for positioning and communication. “Innovations to satellite communications and global positioning systems have facilitated the expansion of maritime operations worldwide,” explains Bagle. “Some technologies are truly impressive. Still, they constitute complex systems which necessitate international cooperation on a range of issues, among them standards on training and equipment.”

AS ABOVE, SO BELOW

Sea Island is using technological innovation by integrating Garmin LiveScope Sonar into its boating fleet. This state-of-the-art sonar system offers anglers unprecedented clarity and precision in underwater imaging.

“LiveScope Sonar is revolutionizing our fishing expeditions,” says Captain Reid Williams, Assistant Manager at Sea Island Yacht Club. “It’s like having a window into the underwater world and gives anglers an entirely new way to connect with the environment.”

“LiveScope Sonar is revolutionizing our fishing expeditions,” says Captain Reid Williams, Assistant Manager at Sea Island Yacht Club. “It’s like having a window into the underwater world and gives anglers an entirely new way to connect with the environment.”

Garmin LiveScope Sonar provides vivid, stabilized imagery with customizable views and three directional modes, allowing anglers to locate and observe fish behavior in real time. Much like how navigational tools transformed seafaring centuries ago, LiveScope Sonar is reshaping how fishing is approached on these storied waters.

“While this technology is undeniably a game-changer,” adds Williams, “it doesn’t replace the expertise of our guides—it enhances it.”

For Sea Island captains, the sonar is about adding to a lifetime of knowledge. Decades spent navigating shifting tides, seasonal migrations and subtle changes in water conditions inform every fishing expedition. The LiveScope Sonar provides captains with an additional tool, helping them to adapt even more effectively and ensure members and guests have the best possible experience.

Captain Williams sums it up: “Fishing here is as much an art as it is a science. The LiveScope Sonar helps us to see more, but it’s the human element—our history with these waters and our passion for sharing them—that makes each trip special.”

Captain Clay Fordham, Master Captain at Sea Island.

CURRENT KNOWLEDGE REQUIRED

Despite advances in technology, there’s no substitute for the navigational wisdom that comes from a deep knowledge of real-time conditions. Anyone who’s had the pleasure of sailing aboard a cruise ship, or who’s watched a freighter enter a harbor knows that even experienced captains sailing giant vessels rely on the intimate knowledge possessed by local harbor pilots to safely bring their ships in and out of port.

St. Simons Island Lighthouse

“Local knowledge is a critical part of the equation when considering how to navigate a waterway,” explains Captain Clay Fordham, Master Captain at Sea Island. “Beyond GPS and automation, the human element is essential to every trip. Technology is an aid to navigation, but should not be solely depended on. Coastal landscapes and currents are always shifting and I learn something new every time I am on the water.” This respect for, and deep commitment to acquiring that knowledge is perhaps the very essence of what links ancient mariners to the sailors of today.

Regardless of technological advances, the art of navigation remains a timeless pursuit. It is a discipline of patience, precision and adaptability, where tradition and innovation must work in tandem to chart a course into the future. The horizon will always beckon, and as long as there are those willing to answer its call, the legacy of navigation will endure, connecting generations of seafarers across the waves.